Improved Monitoring in the World’s Largest Tuna Fishing Ground

You can’t fix what you can’t track. That’s why monitoring is the backbone of developing sustainable tuna fisheries and, ultimately, healthy oceans. From catch composition and bycatch statistics to monitoring compliance of vessels with national or international management measures — observing, measuring, assessing and reporting what’s happening on the world’s commercial fishing vessels at sea is critical work. For many fisheries, this work is done by human observers aboard boats, and the data they collect are essential to achieving the objectives of the organizations charged with protecting our ocean resources.

A one-size-fits-some solution?

But what happens when boarding a vessel is less than ideal for a human observer, if not impossible? On some fishing boats, challenges such as limited space, logistics, safety concerns, and cost can be a serious impediment to deploying human observers. One example is some longline tuna fleets, where these factors have resulted in human observer coverage being less than 2% in some regions. For these fisheries, human observers are not the complete solution to improved data collection and monitoring.

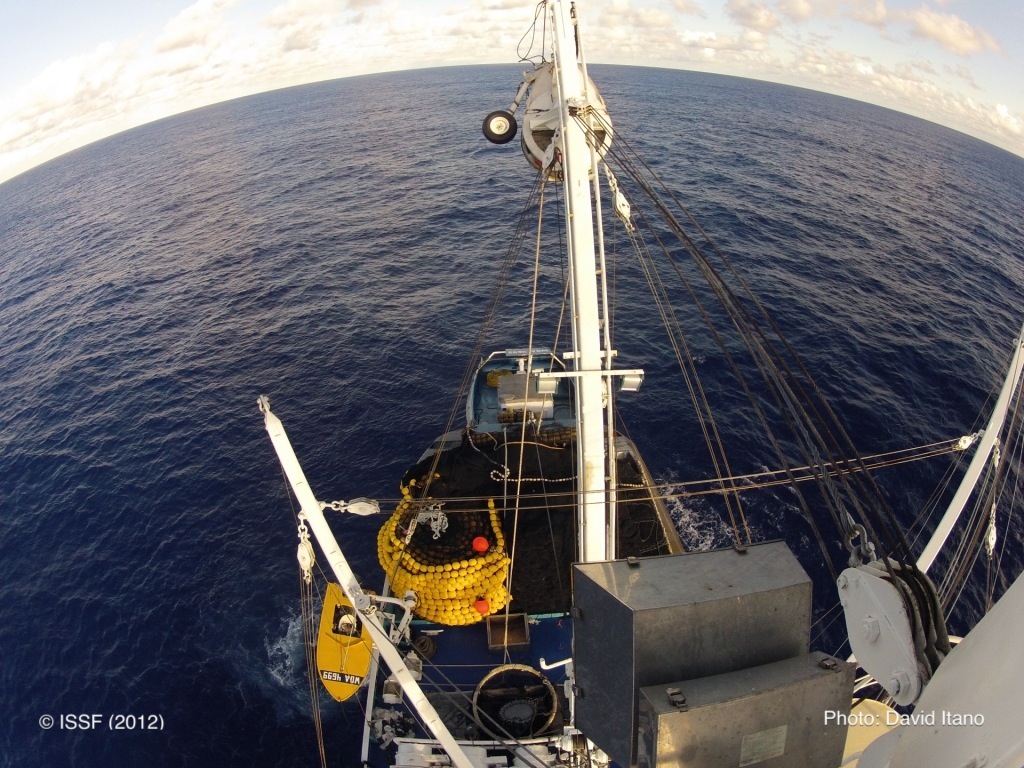

Enter electronic monitoring systems (EMS). These systems include several still or video cameras and sensors installed on a fishing vessel to record activities and data on board, such as images, location, course and speed of the vessel at all times. For many fisheries, EMS have become a reliable alternative or complement to human observer coverage, and a well-proven technology thanks to pilot projects in many parts of the world. In other fisheries, the basics of electronic monitoring continue to be tested and refined – this is the case for tuna longline vessels.

A recent series of pilot projects in Fiji deployed EMS on longline vessels fishing in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. These projects are an example of how partners are building on the successes of previous pilots to upscale EMS across all tuna fisheries. Several groups collaborated on the pilots, and these and related projects have been conducted via partnerships amongst numerous entities — the Government of Fiji and FAO through the Common Oceans /ABNJ Tuna Project funded by GEF and in collaboration with Fijian tuna longline associations.

Next Steps: Coordination, Standardization

The benefits of electronic monitoring as a complement to human observers are multiple. Besides the fact that electronic systems can be placed on small vessels that do not have space for a human observer, these systems can monitor different areas of a vessel at the same time, and operate as many hours per day as needed. And the images and other data can be stored for a long time and reviewed multiple times.

Yet the potential effectiveness of EM cannot be fully realized without regional coordination. That’s why, in the case of advancing EM in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO), the science provider to the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), SPC, is working on a coordinated approach, with funding from ISSF and other groups. From the recent Fijian longline vessel trials to other pilots in the Solomon Islands, stakeholders are partnering in these efforts to improve data collection and analysis, and monitoring, control and surveillance.

SPC is uniquely positioned to help coordinate between the various regional bodies and national authorities to avoid a patchwork of incompatible systems that don’t talk to one another. This latest work expands on a long-standing collaboration on many science and research efforts in tuna fisheries. For example, ISSF also worked with SPC to create an electronic logbook called the eTUNALOG as a way for captains to enter and transmit data directly to authorities. ISSF and SPC continue this close collaboration to ensure consistency in the efforts towards more sustainably managed fisheries.

Fishery experts as well as our partners agree that a system-wide upgrade of data collection and transmission is within the realm of the possible and will have a major positive impact on data quality and usage. The bottom line: the more collaborative and coordinated pilot programs and research we do, the closer we are to improving fishery data reporting across all regions.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Malo Hosken is with the Oceanic Fisheries Programme, the Pacific Community (SPC-OFP).

For more information on EMS trials, check out the Report on the Solomon Islands Longline E-Monitoring Project.

For the results of a recent global workshop on electronic monitoring on longline vessels, check out the following ISSF technical report: http://www.iss-foundation.org/knowledge-tools/reports/technical-reports/download-info/issf-technical-report-2016-07-international-workshop-on-application-of-electronic-monitoring-systems-in-tuna-longline-fisheries/

Editor’s Note: This blog was updated July 27 since its original posting to reflect more accurate pilot project details.