Research Insights to Help Protect Sharks and Mobulid Rays in Tuna Fisheries

By Dr. Melanie Hutchinson

2018 was another busy year for ISSF’s scientific field teams conducting shark bycatch and tuna research in three oceans.

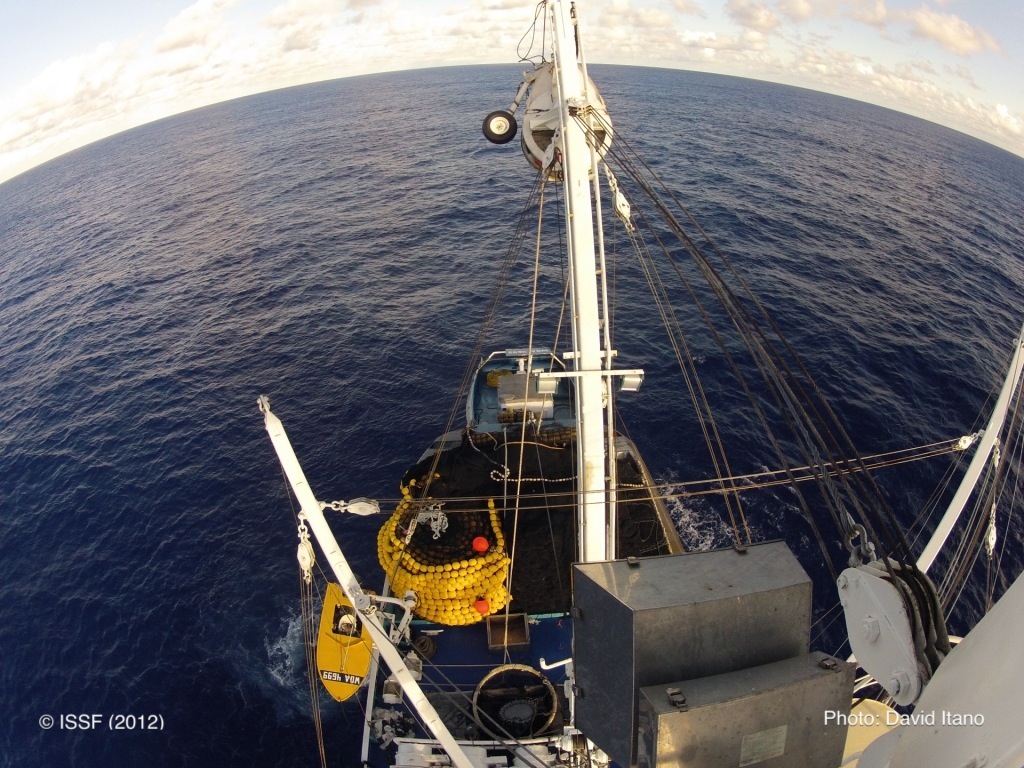

In the Atlantic Ocean, for example, researchers from the University of Hawaii, AZTI in Spain, and the University of Rondônia in Brazil worked with the Curazolean purse-seine vessel Pacific Star.

Our objective for this research cruise was to build on previous ISSF Bycatch Project work showing that silky sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis) released from the net while still free swimming typically survive. In contrast, when sharks are brought onboard and released from the vessel, post-release survival rates are 16% at best.

In the Atlantic, we set out to further examine the efficacy and safety of removing sharks from the net by fishing them out with handlines, an idea that came from a skipper in one of ISSF’s Skippers Workshops. We also wanted to determine if it was practical and effective to have the crew fish sharks out during normal commercial fishing operations.

During a previous Indian Ocean cruise, we had found that fishing the sharks out of the net partially reduced shark mortality: the crew was able to remove and release around 17.2% of the sharks captured. Fishing success varied between 0% and 28.6% of sharks removed when the crew was doing the fishing. The scientists were able to remove up to 34.4% of sharks during different sets, leading us to believe that with repetition and practice, fishers could improve their skill at this method. Safe handling, however, remains an issue.

The 2018 Atlantic Ocean cruise was unique. The vessel was fishing in the waters of Gabon in July, a productive seasonal upwelling zone that attracts a large variety of pelagic predators including sharks. The vessel was more successful fishing on free schools of tuna than fishing on Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs), so instead of catching juvenile silky sharks (which make up ~85% of the shark bycatch in FAD associated sets in all oceans), the shark bycatch in the free-school sets was characterized by schools of adult silky, spinner (C. brevipinna), oceanic blacktip (C. limbatus), smooth (Sphyrna zygaena) and scalloped hammerheads (S. lewini). These sharks were large, not associated with FADs, successfully feeding on small baitfish and tuna — and not interested in the baited hooks and chum we were using for our handline experiments.

During the cruise’s 40 sets, only three were made on FADs, and those were the only times we were able to capture and release any sharks from the net to meet our research objectives. It was frustrating to be out there, knowing how much time and resources had been invested in the logistics of getting our research team onto that vessel. We did make important discoveries, however. We observed phenomenon we had never seen before and had several opportunities to tag species that are rarely encountered, including whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) and chilean devil rays (Mobula tarapacana). We tagged two whale sharks, and both survived the interactions, providing further evidence that the best handling guidelines work for this species.

We also got tags on six mobula that were captured. Despite the crew’s best efforts to get these animals back in the water safely using recommended handling methods, five of the six tagged mobula died post release. Observations of these interactions made it clear that these animals are very large, heavy, unwieldly and difficult to maneuver safely. It took a long time, sometimes over 10 minutes, to get the animal from the brail onto the cargo net and then back into the water. All of the animals that we tagged were alive at release. Some showed visible signs of trauma, including net scars from being in the sack and brail, but all swam away well.

It appears as if releasing animals using the RFMO-adopted best practices may reduce mortality in a small percentage of mobulids that are brought onboard the vessel, but the physiological impacts of the interaction cause delayed mortality in a larger proportion. As many mobulid populations are considered to be vulnerable or endangered, avoiding mobulid “hot spots” while fishing, or releasing them from the sack or while the net is still open, are the only viable means of substantially reducing purse-seine fishing’s impact on these populations. However, it should be noted that purse-seine fishing is not the main threat to these populations.

Opportunities like these, to get tags on species that are in trouble and hard to study, are priceless. As one of the authors of the best handling practices for rays and mobula adopted by the WCPFC in 2017, I was very disappointed to see firsthand that we had missed the mark. But now we have tagging data to show that we need to revisit our recommendations and implement new or additional guidelines that will have the desired effect of reducing mortality for incidental mobulid encounters. At-sea cruises provide good stepping stones for further work and remind us that improving fishing practices is an iterative process.