Electronic Monitoring in Indian Ocean Tuna Fisheries

A new report, “Minimum standards for designing and implementing Electronic Monitoring systems in Indian Ocean tuna fisheries,” co-authored by scientists from ISSF, AZTI and the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), was recently presented to the IOTC Scientific Committee as an important step in accelerating the use of electronic monitoring systems across Indian Ocean tuna fisheries. The paper seeks to help electronic monitoring systems (EMS) “be fully accepted as a data collection mechanism that provides independent observations of a scientific nature,” said report co-author Fabio Fiorellato, IOTC Data Coordinator.

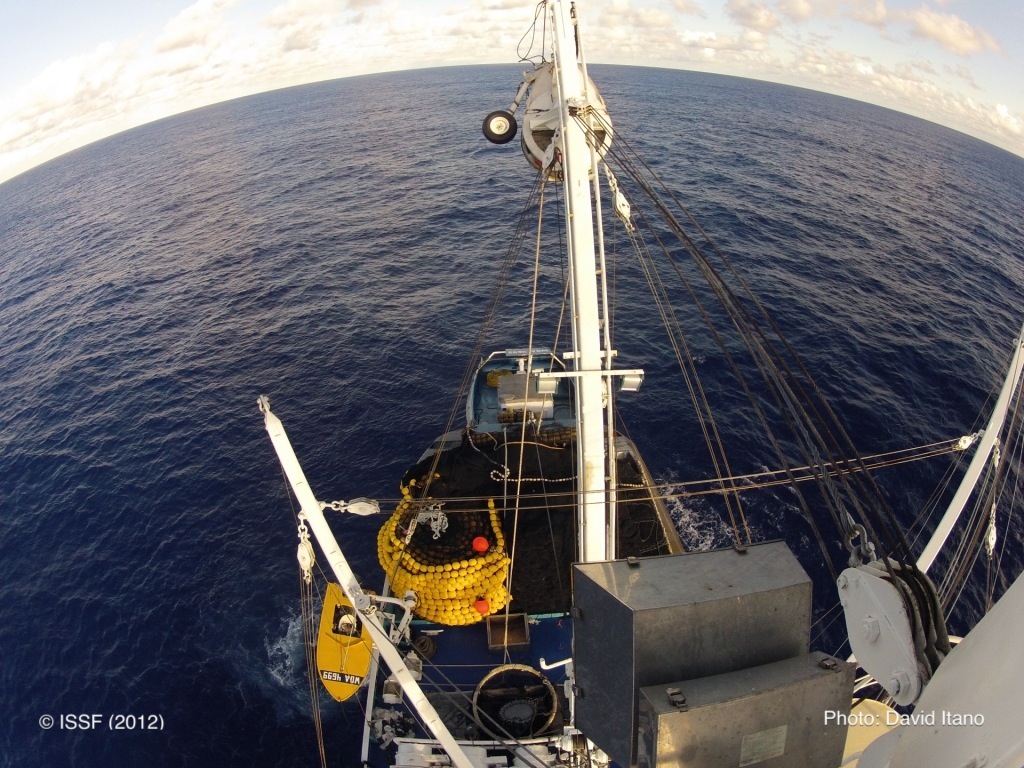

Electronic monitoring (EM) through the use of cameras and other sensors is a proven technology that has been increasingly employed for various purposes on fishing vessels, primarily in industrial fleets. Electronic monitoring systems (EMS) include equipment that tracks a vessel’s position and activity, together with cameras that record key aspects of the fishing operations.

“As concern is increasing over exploitation of fish stocks, we should be increasingly turning to novel technologies to improve our scientific data collection. EMS provides just such an avenue for advancement,” commented Paul de Bruyn, Science Manager, IOTC, in response to the report publication. “EMS has proven to be an incredibly effective way to supplement human observers — to increase the coverage and sampling required to obtain scientific information in order to provide better management advice for target and bycatch species in fisheries.”

The paper outlines minimum requirements for a standard EM system in Indian Ocean tuna fisheries, addressing elements such as technical equipment, data storage and autonomy, hard drive chain of custody, and office observer training and qualifications. Photographs and diagrams of electronic monitoring systems and equipment on purse seine, longline, and pole-and-line vessels illustrate the report. “EMS requirements change sensibly with gear and vessel type, in particular for what concerns the configuration of imaging devices,” said co-author Fabio Fiorellato, IOTC Data Coordinator.

The paper also evaluates EMS’ capabilities to collect the IOTC regional observer scheme (ROS) minimum standards data fields in line with the IOTC’s latest requirements, “because EM equipment should be tailored to each vessel based on performance to meet program objectives,” as lead author Hilario Murua from ISSF emphasized.

With the COVID pandemic forcing tuna RFMOs to suspend observer programs, the implementation of electronic monitoring systems across all tuna fisheries is especially critical today both for scientific and compliance purposes. “EM minimum standards depend on the objective of monitoring; scientific versus compliance purposes,” said Gerard Domingue, IOTC Compliance Manager.

“The need for human observers will continue in the future,” commented de Bruyn, “but EMS is a fantastic way to increase or supplement observation coverage on large vessels while providing an option for having coverage on small vessels for which the deployment of human observers is not feasible.”